I have been involved with the restoration of 5 stamp mill bull wheels, from a 4 foot wheel to 7 foot wheels. The extent of the restoration also varied from a cosmetic replacement, replacing the outer crown of the wheel and total rebuild of the wheel and the hub.

I will go over the most extensive bull wheel that was done for the Cave Museum

Inspection of the 7’ Bull Wheel identified that all of the wood would have to be replaced and there was a serious crack in the hub and the inner flange that would have to be replaced . The initial conditions are shown below.

We had to machine the hub from a piece of 9” bar stock and the inner flange was cut from 1” steel plate, the center drilled out for the flange and two keyways machined into the hub below.

We used 5 layers of 1 ¼” exterior tongue and grove plywood for the core of the bull wheel that were glued and nailed together with Gorilla Glue. We placed pie shaped pieces around both sides of the plywood to make it look like the original wheel.

We installed the 7 foot X 8” wheel on the hub and then installed it on the camshaft. The perimeter of the wheel was trued-up by using sanders.

Next we started installing the crown of the wheel that was made up of 2”X12” lumber cut in a semi-circle, making it an 8” wide piece that overlapped the wheel by 4”, then glued and nailed it to the inside of the wheel.

Once the outer ring was installed, we started to fill in the center sections of the outer wheel with semi-circles made out of 2” X 6” lumber cut in a semi-circle, making it a 4” wide piece, that came out even with the outer ring just installed. Each piece was glued and nailed in place.

When the center of the wheel was covered with the 4” semicircle pieces, then they went back to the 8” semicircles around the outside part of the wheel as shown below.

When we completed the outside layer, then we installed one more layer on both sides that we had just completed. This is shown in the picture. The wheel ended up being over 14” thick. We treated all of the wood on the wheel with wood aging and epoxy treatments to make the wheel last forever.

We used a shop electric plane that we removed from its stand and mounted to scaffolding to make the outer face of the bull wheel true and balanced. The two volunteers are manually rotating the wheel past the plane to remove any inconsistencies from the wheel's surface.

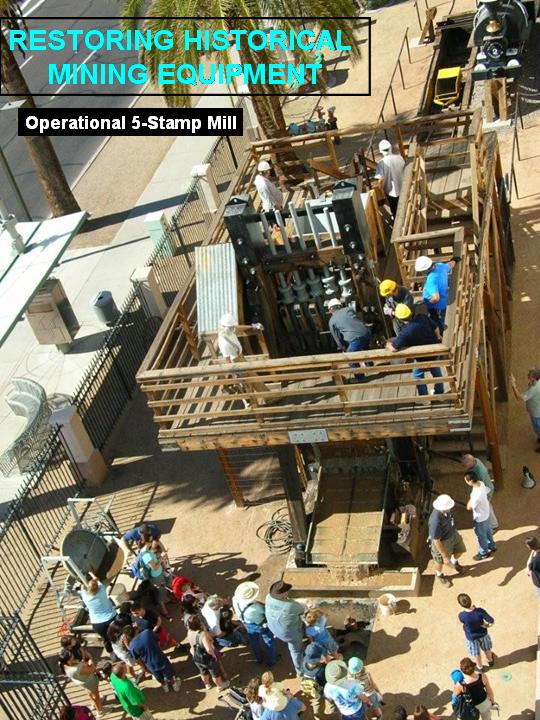

Below is a picture of the bull wheel Installed on the Golden Reef Mine 10-stamp mill at the Cave Creek Museum, Cave Creek, Arizona.